Foundations of Field ID: Color Patterns

From bright blocks to subtle streaks, color patterns offer quick and powerful clues for identifying birds

Welcome to the birdy side of the internet! This week’s edition is packed with fresh insights and a special focus on bird ID—our theme for the first week of every month. You’ll find a handy Birding Tip to help you tell Greater and Lesser Yellowlegs apart, plus the newest installment of our Foundations of Field ID series, where we’re exploring color patterns. Each piece is built to stand on its own, but together they create a growing foundation for stronger, more confident birding. Think of them as your Birding University crib notes—quick, helpful, and just the beginning of what’s to come in the Birding University ecosystem.

This Week in Birding History: Shorebirds at Lake Abert

July 12, 1996 — Twenty-nine years ago this week, birders Mike and MerryLynn Denny reported an amazing number of shorebirds from Lake Abert in south-central Oregon: 26 Black-necked Stilts, 115 Western Sandpipers, 812 American Avocets, 15,000 Wilson’s Phalaropes, and 35,000 Red-necked Phalaropes among other species. The Red-necked Phalarope count still stands as Oregon’s highest tally. Lake Abert also hosts state high-count records for Cinnamon Teal (1,000), Black-necked Stilt (8,350), Northern Shoveler (20,000), Eared Grebe (30,000), and Wilson’s Phalarope (330,000).

According to eBird data, birders submit fewer checklists in July than almost any other month of the year. Yet July can be an exciting month for North American birding with fledgling landbirds birds on the move, wading birds dispersing northward, adult shorebirds moving south, and vagrant wanderers appearing in unexpected locations. We encourage you to get outside and look for anything unfamiliar or unusual!

Birding Tip: Yellowlegs ID

As the breeding season winds down, many birds begin their journeys to their wintering grounds. Across North America, among the first species to depart the Arctic and Boreal regions are shorebirds. With southbound migration often kicking off by mid-summer, now is the perfect time to brush up on your shorebird ID skills, starting with two of the most widespread and deceptively tricky species: Greater and Lesser Yellowlegs.

First, make sure you’re looking at a yellowlegs to begin with. Look for long, bright yellow legs and a relatively long, straight bill. In flight, yellowlegs show uniform gray wings and a white tail with fine gray barring. These features help distinguish them from similar shorebirds, such as Willets, Solitary Sandpipers, or Wilson’s Phalaropes, all of which exhibit different, albeit sometimes subtle, patterns in their wings or tails.

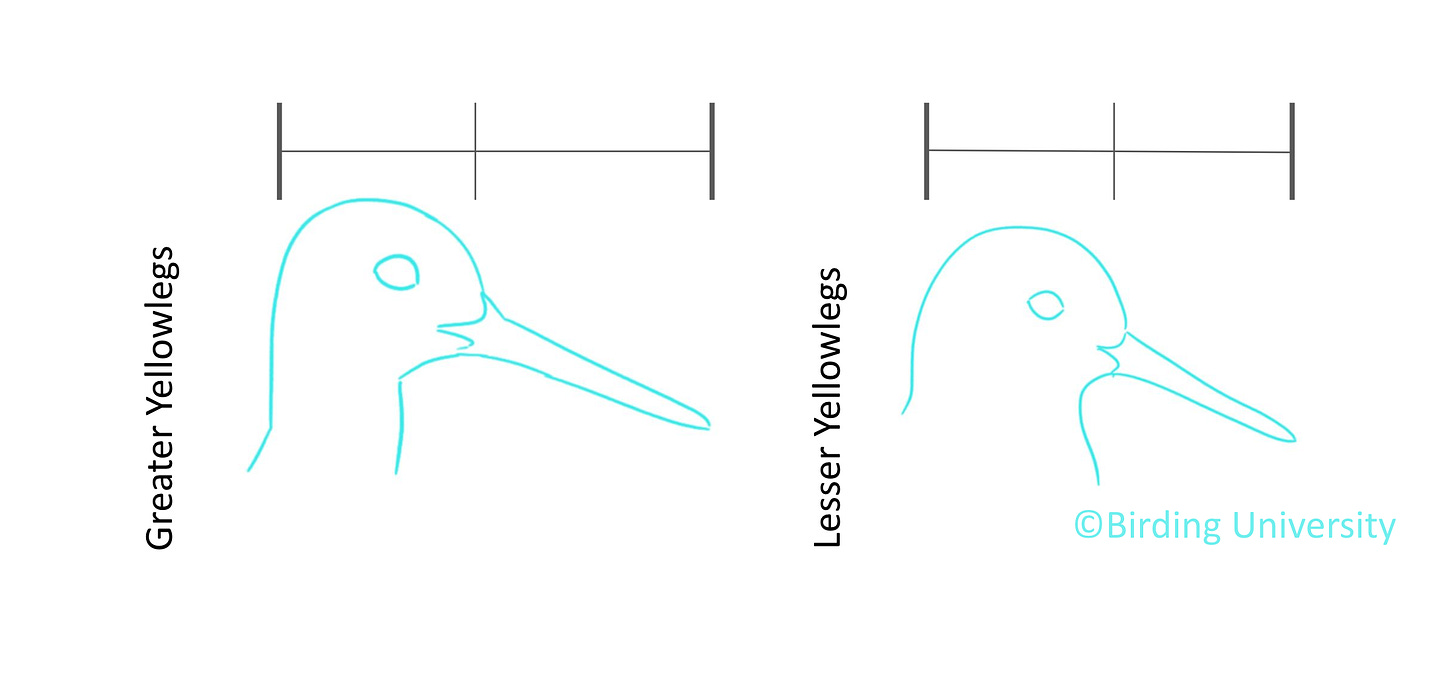

Once you’ve narrowed down a mystery shorebird as a yellowlegs, the next step is distinguishing between Greater and Lesser—a classic challenge, even for experienced birders. Here’s how to approach the ID process with confidence.

Size and Shape

Structure is the most reliable starting point for this comparison. Unlike plumage, shape doesn’t change with light or molt, and it holds up even when birds are in nonbreeding plumage.

Greater Yellowlegs

This is the larger of the two, characterized by a longer and thicker bill that is often turned up slightly at the tip. Importantly, the bill of a Greater Yellowlegs is usually longer than the length of the bird’s head, that is, from the back of the head to the forehead, sometimes slightly, sometimes dramatically. In terms of posture, Greaters often exhibit a distinctive S-curve in the neck, characterized by a bulging lower neck and a sharp angle where the neck meets the back. Be aware that a bird’s movements can influence this and may be somewhat subjective at times.

Lesser Yellowlegs

Lesser Yellowlegs are smaller overall, with a thinner, straight bill that is approximately equal in length to the head. Their posture is more upright, with a straighter neck and a gentler, more obtuse angle between the neck and back. At times, a steep forehead may be visible, though this field mark is variable and should be used with caution.

Color and Plumage

The plumage is often less helpful, as both species resemble each other, especially in their basic (non-breeding) plumage. Still, there are a few subtle differences that can support your ID.

Greater Yellowlegs

In breeding plumage, Greater Yellowlegs often show heavier and more extensive barring along the flanks, though this can vary between individuals and is best used alongside other field marks. Their bill also tends to be paler overall, sometimes appearing grayish or even with a slight greenish hue, especially near the base.

Lesser Yellowlegs

Overall, Lesser Yellowlegs tend to look cleaner along the sides than Greaters during the breeding season with less extensive flank barring. Juveniles of both species resemble their nonbreeding adults but have browner upperparts with more evenly distributed pale spotting and subtle breast streaking. To distinguish juvenile Lesser Yellowlegs from juveniles of Greater Yellowlegs, note that the breast and neck streaks on Lesser Yellowlegs are paler, grayer, and less distinct. Additionally, Lesser Yellowlegs typically have a darker bill, ranging from slate-gray to black.

Pro tip: While plumage often steals the spotlight in bird ID, don’t overlook a bird’s bare parts—the eye color, eye ring, bill, gape, legs, and feet. These fleshy features can reveal important details, helping you age a bird and distinguish it from similar-looking species.

Voice

Calls can be an excellent field clue, especially during migration. Both species give a sharp ‘tu’ or ‘tew’ note, especially in flight. The key difference? The number of notes.

Lesser Yellowlegs: Usually 1–2 notes (tu-tu)

Greater Yellowlegs: Typically 3 or more notes (tu-tu-tu or tu-tu-tu-tu)

While tonal differences do exist—Lesser Yellowlegs’ flight call tends to be flatter and softer—they’re subtle. In most cases, simply counting the number of notes is your most reliable method.

In the Field

You won’t always have the perfect angle, ideal lighting, or a direct side-by-side comparison in the field. However, by combining clues—such as structure, posture, relative bill size, and a bird’s flight call—you can often make a confident identification. Try not to rely too heavily on any single feature, especially when views are brief or unclear. Birds vary, and even experienced birders sometimes walk away uncertain of a tricky yellowlegs. That’s perfectly fine. It’s always better to record a bird as “yellowlegs species” [Lesser/Greater Yellowlegs in eBird] than to guess when unsure. Shorebird ID is a lifelong journey, and the more you watch these graceful migrants, the easier it becomes to tell them apart.

Foundations of Field ID: Color Pattern

Welcome back to Birding University’s four-part series on the foundations of bird identification. Last month, we focused on size and shape—the silhouette of a bird. This month, we turn to another key tool: color pattern.

Like shape, color offers quick, powerful clues. But beginners often get lost chasing tiny feather details, trying to match a bird to a field guide photo’s finer marks. Skilled birders focus instead on the big picture—blocks of color, bold contrasts, and patterns of light and dark. Think patterns, not particulars.

The beauty of color patterns? They’re flexible. A long look may reveal fine details, but even a glimpse can be enough. Take the Red-headed Woodpecker. When viewed, its crimson head is unmistakable. But even if it flashes by in flight, slipping between trees, those black wings with bold white patches across the back and tail can still lock in the ID.

Editor’s note: Color can be deceiving. Light, angle, and background all play tricks on the eye. A gull’s gray back may look silver in the sun or charcoal in shadow. A Warbling Vireo in green foliage might seem yellowish, resembling a Philadelphia Vireo. And remember—field guides often show birds in ideal light and perfect plumage. Real life rarely does.

Understanding Color Layout

Some species wear a single color from head to tail, such as the American Crow or Great Egret. Others carry just two key tones, like the vivid red and black of a male Scarlet Tanager. Still others, like male Painted Buntings, display bold blocks of multiple colors across their entire body.

Often, just one body part holds the key. Northern Harriers and Northern Flickers flash telltale white rumps in flight. American Redstarts fan fiery orange tail patches as they forage, scaring up insects. These small, concentrated bursts of color can be all you need, even in motion.

When it comes to visual impact, some species are high-contrast and unmistakable. Male Yellow-headed Blackbirds dazzle with bright yellow heads, black bodies, and white wing patches. Sparrows in the genus Zonotrichia—White-throated, White-crowned, Golden-crowned, and Harris’s—have bold, distinctive head patterns that pop even at a glance. Others species are subtler, but colors and patterns can still confirm an ID. Song Sparrows wear thick, smudgy chest streaks with a central spot. Lincoln’s Sparrows show fine, crisp lines over a warm buff wash. Same palette—very different effect. It’s the difference between a charcoal sketch and a fine ink drawing.

Where the Patterns Fall

Placement matters as much as color itself. Male Mallards and Northern Shovelers both have green heads and multicolored bodies. But Mallards wear rusty-brown chests and gray flanks, while Shovelers have bright white chests and rusty sides—like a reversed layout. That shift alone can separate them at a glance.

Or take Lazuli Buntings and Western Bluebirds. Both are blue and orange with white below, but Lazulis shows bold white wing bars. Bluebirds don’t. That single detail makes the difference when you see a silent bird teed up at a field’s edge.

Practice & Progress

Start with overall patterns—they’re as fundamental as size and shape. Then, refine your eye with more focused observations. Try taking a “color inventory” of the birds you see, especially on the wings and head, where useful field marks often cluster.

When watching a mystery bird, ask:

How many blocks of color do I see?

Where is the color concentrated?

Are the patterns bold or faint?

Do the tones contrast sharply or blend?

Where does color flash when the bird moves—tail, wings, rump?

On the wings, look for bars, patches, or edging, if anything is present at all. On the head, watch for color blocks on the crown, eyebrow stripes, spectacles, lores, or malar stripes. And don’t worry if you don’t know the terms—look for patterns. Names come with time, and helpful diagrams of a bird's feather topography are just a quick search away (BU will also cover this in the future).

And don’t forget: some birds don’t need a label to be worth the look. Painted Buntings, Mountain Bluebirds, tanagers, hummingbirds, and orioles wear their brilliance out loud. For them, color isn’t just a clue—it’s part of the magic.

What’s Next?

In August, we'll continue our Foundations of Field ID series with behavior—how posture, movement, and personality can be just as telling as plumage.

Weekly Poll

Thanks for Reading

We hope this week’s newsletter helps you see birds with fresh eyes and gives you something new to look for on your next walk. Let us know what stood out or what questions you still have—we’re always here to help.

* Please visit Phil Stollsteimer Photography for more amazing bird photography.