Celebrating Checklists: AviList and 2 Billion eBird Observations

How global community and collaboration are shaping checklists—cornerstones of birding and avian conservation

Welcome to the birdy side of the internet! From the pioneering observations of Charles Darwin to the latest breakthroughs in global bird taxonomy, we hope this issue equips you with the knowledge and inspiration to support birds and their habitats through natural history, birding, and thoughtful list-keeping. We’ll explore natural history principles that sharpen your birding skills, celebrate eBird’s recent milestone of two billion observations, and introduce AviList — a unified global bird checklist reshaping how we identify, communicate about, and protect birdlife.

This Week in Birding History: Darwin Contemplates the Ostrich

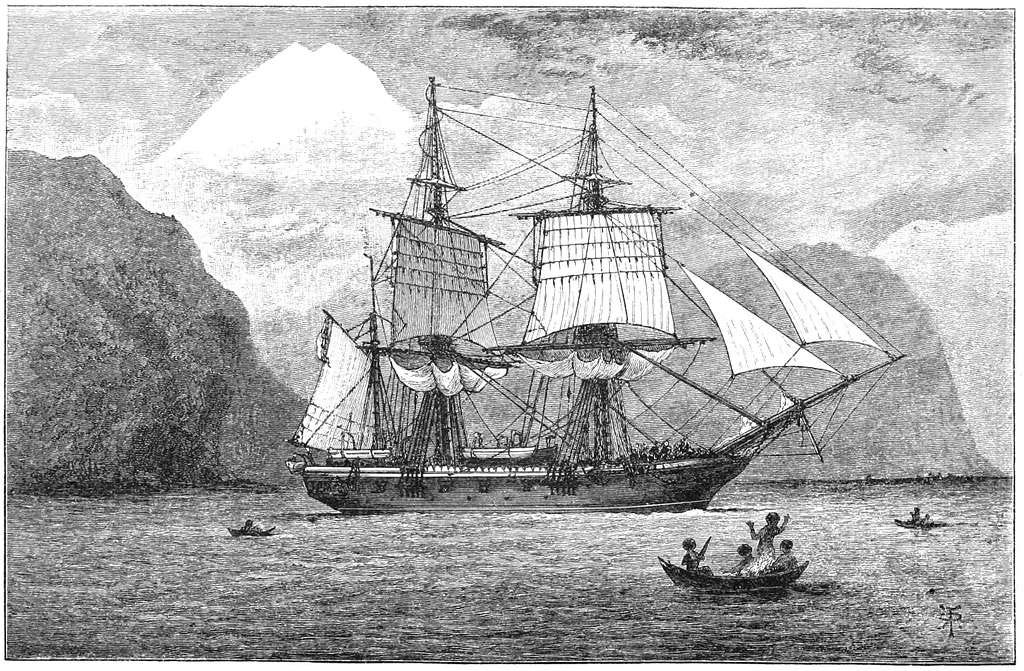

June 18, 1836 — One hundred eighty-nine years ago this week, Charles Darwin departed South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope after a 19-day excursion, marking his final research stop aboard the HMS Beagle. While best known for his work on the theory of natural selection, Darwin’s insights were shaped by far more than Galápagos finches. He wrote extensively about flightless birds during his voyage, including rheas in South America, the Flightless Cormorant (Nannopterum harrisi) in the Galápagos, Flightless Steamer-Ducks (Tachyeres pteneres) in Argentina, cassowaries and emus in Australia, kiwis in New Zealand, and ostriches in South Africa. Reflecting on the ostriches he observed in South Africa, Darwin wrote the following:

“as natural selection increased in successive generations the size and weight on its body, its legs were used more, and its wings less, until they became incapable of flight.”

Birding Tip: Using Natural History to Improve Your Birding

Natural history is the study of biodiversity, grounded in observation rather than experimentation. It seeks to uncover patterns within the apparent randomness of ecological systems. When applied to birding, natural history offers a mental framework that sharpens observational skills and deepens understanding. The principles of natural history span a wide range of topics, explaining phenomena from the exceptional biodiversity of the Andes (Janzen’s Rule) to the long-distance migrations of Arctic-breeding shorebirds (Rapoport’s Rule). In general, building a strong foundation in natural history can refine your approach to bird identification. Below, we explore three key principles to help guide your practice in the field.

Allen’s and Bergmann's Rules

Allen’s and Bergmann’s rules both describe how climate influences the physical characteristics of animals, particularly in relation to temperature. Allen’s rule posits that in colder climates, appendages—such as legs, ears, and bills—tend to be shorter to conserve body heat, while in warmer climates, longer appendages help dissipate heat. Bergmann’s rule, on the other hand, states that endothermic animals tend to have larger overall body sizes in colder regions, aiding in heat retention due to a smaller surface area-to-volume ratio.

While these patterns may seem subtle or even trivial, they can be powerful tools in the field. Imagine scanning a group of terns during migration and spotting one with noticeably shorter legs. That detail could be a clue: a high-latitude breeder like the Arctic Tern, tucked among more temperate Common Terns. Similarly, body size differences linked to Bergmann’s rule can help separate Snowy Owls from American Barn Owls. Though both species share pale plumage, the Snowy Owl, adapted to Arctic conditions, is significantly bulkier.

These principles become especially useful when applied together. Canada and Cackling Geese, for example, are notoriously difficult to differentiate. But their distinctions—Canada Goose’s longer neck and bill versus Cackling Goose’s compact, stubby form—align with Allen’s and Bergmann’s rules and reflect their respective breeding ranges. Understanding these ecological patterns enables birders to look beyond plumage and song, instead using evolutionary adaptations as a guide to identification.

Gloger’s Rule

Gloger’s rule suggests that animals living in more humid environments tend to have darker pigmentation than those in arid regions. In birds, this often translates to darker plumage in wetter habitats. While this pattern may not seem particularly useful for identification, since birds from drastically different climate zones are rarely seen together, it can still be helpful, especially during migration or in transitional habitats.

A common identification challenge where Gloger’s rule applies is distinguishing between Song and Savannah Sparrows. Song Sparrows, which are often associated with wetter, shrubbier, or marshy habitats, typically show heavier, more blurred streaking and darker overall tones. In contrast, Savannah Sparrows, which favor grasslands and drier open areas, usually appear thinner, with sparser streaking, giving them a paper-like appearance.

Another subtle but instructive example is found in the Sooty and Dusky Grouse, which were formerly considered the same species as the Blue Grouse. The Sooty Grouse breeds in the moist forests of the Pacific Northwest and has darker, duskier plumage, whereas the Dusky Grouse inhabits drier inland and montane forests, being paler in color. These differences, though subtle, are consistent with Gloger’s rule and can offer a valuable clue when trying to separate similarly shaped or behaving species, especially when other cues are ambiguous.

While these principles won’t make tricky identifications effortless, and there’s often many other tools available, such as range maps, they offer an invaluable framework from which to begin. Thinking like a natural historian means asking not just what a bird looks like, but why it looks that way—what ecological pressures and evolutionary histories have shaped its form. Over time, these patterns become mental shortcuts: a larger body size may indicate a colder breeding origin, while darker plumage might suggest a more humid environment. Rather than relying solely on field marks in a guide, you’re using climate, geography, and biology to narrow the field before the bird even lands. The more you internalize these natural history principles, the more intuitive your identifications become—and the more connected you feel to the evolutionary story behind each bird you encounter.

Bird’s Eye View: eBird Surpasses 2 Billion Bird Observations

Since its launch in 2002 by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the National Audubon Society, eBird has grown into arguably the most comprehensive community science project in history. On Monday, June 2, 2025, eBird reached a remarkable milestone: over 2 billion bird observations had been submitted worldwide. The two-billionth bird was one of three Tropical Kingbirds (Tyrannus melancholicus) recorded on a checklist from Atlántida, Honduras. This landmark moment highlights the extraordinary collective power of birders, from backyards to the most remote wildlands, who advance science and conservation with every checklist they submit.

The two-billionth sighting represents more than a number; it marked a real-time connection—one of countless moments shared by passionate birders around the world, whether of rare species or familiar favorites. Each observation adds a pixel to the ever-evolving picture of bird distribution, migration, population trends, and habitat health.

Why is this incredible? Reaching two billion entries reflects not just volume, but velocity—the leap from one billion in 2021 to two billion in just a few years marks an extraordinary acceleration in global participation. That exponential growth fuels more detailed trend analyses, sharper insights into migration and distribution, and more effective conservation strategies. It’s not merely a milestone—it’s a testament to the power of community-driven science to shape the future for birds and the ecosystems they depend on.

AviList: A New Era in Global Bird Taxonomy

After centuries of fragmented classification systems, global bird taxonomy finally rests on a unified foundation: AviList, a single, harmonized checklist of the world’s birds. Released this week, AviList is the result of years of collaboration among leading authorities in ornithological taxonomy, nomenclature, and bioinformatics. For the first time, representatives from the American Ornithologists’ Society, Avibase, BirdLife International, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and the International Ornithologists’ Union have collaborated to produce a globally agreed-upon taxonomy, designed to enhance data sharing, streamline information systems, and support more effective conservation efforts worldwide.

Developed through meticulous review and broad consensus, AviList currently recognizes 11,131 bird species, 19,879 subspecies, 2,376 genera, 252 families, and 46 orders. These figures represent more than a tally—they reflect a recalibrated understanding of avian biodiversity. Rooted in an integrative species concept, AviList synthesizes data from morphology, genetics, vocalizations, behavior, and biogeography to provide a clearer understanding of evolutionary relationships. In some cases, this has led to taxonomic changes with recognizable implications. For example, the Hudsonian Whimbrel, once considered a subspecies (Numenius phaeopus hudsonicus), is now recognized as a distinct species (Numenius hudsonicus), exemplifying how AviList reshapes both scientific understanding and future conservation priorities.

For birders, the implications are immediate and wide-reaching. Synergy among field guides, regional checklists, and platforms like eBird have long been hindered by inconsistencies among central taxonomic authorities (IOC, Clements, BirdLife). AviList provides long-awaited alignment, establishing a unified scientific language for life lists, checklists, and identification resources worldwide. The result is fewer taxonomic surprises and greater consistency across platforms, including eBird, which is already 99.99% aligned with AviList.

From a conservation standpoint, the unification is equally transformative. Environmental laws, treaties, and threat assessments often rely on taxonomy to define and protect species. When organizations work from mismatched lists, species can be overlooked or underprotected. AviList provides a unified framework that enables conservationists, governments, and NGOs to track and safeguard bird species more effectively across international borders. As BirdLife International and the IUCN Red List begin integrating AviList—a process that may take up to five years—global conservation efforts stand to become more coordinated, comprehensive, and impactful.

AviList will be updated annually and remains freely accessible at avilist.org. The inaugural 2025 version is now available for download in both detailed and simplified formats, complete with transparent decision summaries and extensive references. Whether you're a backyard birder or a professional ornithologist, AviList offers a vital new tool for understanding and conserving the world's birds. As science progresses and avian diversity continues to evolve, this unified list will evolve with it, offering a shared foundation for research, conservation, and discovery in the decades to come.

Editor’s note: Birding University welcomes AviList as a major step toward unifying global bird taxonomy and advancing conservation. At the same time, we recognize that no checklist—no matter how rigorous—is perfect. Some in the birding community have raised thoughtful concerns about version 1, including naming decisions, regional differences, and cultural sensitivity. These conversations are both expected and necessary. Fortunately, AviList includes a transparent, standardized proposal process for future revisions, inviting input from scientists and birders alike. This community-driven approach ensures that the list will continue to evolve and improve over time, meeting the needs of people and birds.

Weekly Poll

If you answered yes (or somewhat), we’d love to hear more. Are you an eBirder? A notebook keeper? Do you list by yard, county, state, and year? Please share your listing style in the comments—Birding University is listening.

Thanks for Reading

Thank you for joining us on this journey through the fascinating world of birds, where history, science, and community come together to help you grow as a birder and steward of the natural world. We appreciate your curiosity, your contributions to community science, and your commitment to conservation. In each issue, we strive to equip you with the knowledge and skills to deepen your birding experience and make a meaningful impact on birds and their habitats. Stay tuned for next week’s edition, where we’ll continue exploring discoveries, practical tips, and stories that inspire and inform.

* Please visit Phil Stollsteimer Photography for more amazing bird photography.

I love keeping a yard list! The smaller the scale the more intriguing the list in my opinion!

I really enjoyed this recent post. Very interesting and informative. Philip's pictures are wonderful.